Remembering Admiral Byrd

By Dehk at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6041845

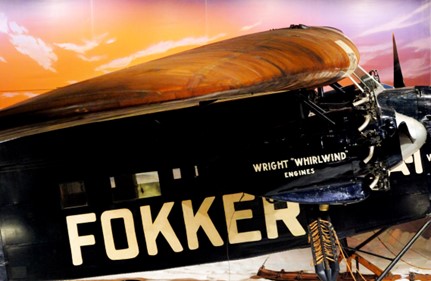

- The Fokker Aircraft Corporation established their America headquarters and factory right here in at Teterboro.

- They built the Fokker F-32 in 1929 here. It was the first four-engine commercial aircraft built in America and the largest land plane in the world.

- It had a capacity of 32 seated passengers and 16 sleeping passengers. From wingtip to wingtip, the massive craft had a wing area of 1,350 square feet. Its length was 69 feet, 10 inches, with a wingspan of 99 feet and height of 16 feet, 6 inches.

- Its high cost – $110,000 – made the aircraft a hard sell from the beginning, especially during the Depression.

Admiral Byrd’s Flights to both North and South Poles

Admiral Byrd was a US naval officer who was a world-wide sensation for his feats as a global explorer. On both his historic flights he piloted a Fokker Tri motor, named ‘The America’.

The plane made of steel tubing, plywood and cloth became a common sight right here at Teterboro as alterations were made by Tony Fokker, scion of the family who manufactured the plane.

Byrd chose the Fokker Trimotor–an American-built version of the Dutch Fokker F.VIII-3M–as the plane for his polar flight. Christened Josephine Ford in honor of backer Edsel Ford’s daughter, the plane was 42 feet 2 inches long with a wing spread of 63 feet 4 inches. Three powerful Wright Whirlwind J4 air-cooled engines producing 200 horsepower each were capable of pulling the aircraft at a high speed of 122 miles per hour. Centered in each wing was a gasoline tank with 100-gallon capacity, while two other tanks in the cabin held 110 gallons each. At cruising speed, fuel consumption was about 28 gallons per hour.

The rig was readied for Adm Byrd’s first flight to the North Pole. On May 9, 1926, Byrd took off from an island in Norway. The flight left from Spitsbergen (Svalbard) and returned to its takeoff airfield, lasting 15 hours and 57 minutes, including 13 minutes spent circling at their Farthest North. Byrd and Bennett claimed to have reached the North Pole, a distance of 1,535 miles (1,335 nautical miles).

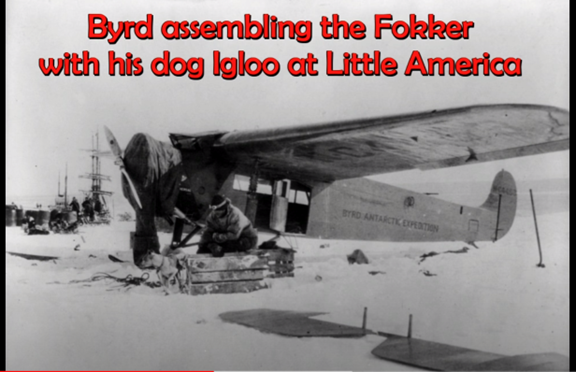

Richard Byrd took three airplanes on his first Antarctic Expedition 1928-29. In March, 1929, he sent three men in the Fokker to the Rockefeller Mountains for geologic studies. A blizzard roared in, hurled the plane in the air, and slammed it down on the ice completely destroying it. The frame of the Fokker is visible today. Byrd’s grandson, Robert Byrd Breyer, is leading a team to recover the plane and return it to the States for display in a museum.

at 9:02 a.m., Josephine Ford passed over the North Pole. Bennett swung the plane to the right to confirm their position on the sextant, then circled and confirmed it twice more. Of his impressions of that historic moment, Byrd wrote: ‘We felt no larger than a pinpoint and as lonely as a tomb; as remote and detached as a star.’

Below them stretched ice fields bordered by pressure ridges built into near impassable tangles of overlapping ice cakes. Separations of ice fields left watery leads ‘which had been recently frozen over and showing green and greenish-blue against white.’

Bennett continued to circle the North Pole, allowing Byrd to reverify their location and to take photos. At 9:15 a.m., Josephine Ford turned back toward Spitsbergen. To the aviators’ surprise, the oil leak stopped and the engine did not seize up and quit. Later they found out that a rivet had pulled loose on the oil tank causing the fluid to dribble out until it went below the rivet’s level. Since there had been plenty of oil in the tank, the loss had not damaged the engine.

Among the dangers Byrd had to contend with were powerful Arctic winds that could easily throw a plane off course. Navigating from the air was also hazardous, since the dazzling white of ice and snow or the Arctic fog made the land seem horizonless against the sky. Landing to take bearings meant setting a craft down on unknown terrain–or no terrain at all, but treacherously deceptive sea ice. Standard compasses functioned erratically in the Arctic. Sub-zero temperatures played havoc with engines. Any expedition forced down faced a perilous trek across ice fields. And, always remember, no one had ever experienced what life would be above the pole—shifting winds and magnetics mad for what was probably a terrifying ride for anyone.

In 1933, Byrd, now a rear admiral in the navy, led a second expedition to Antarctica. During the winter of 1934, he spent five months trapped at a weather station 123 miles from Little America. He was finally rescued in a desperately sick condition in August 1934. In 1939, Byrd took command of the U.S. Antarctic Service at the request of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and led a third expedition to the continent. During World War II, he served on the staff of the chief of naval operations. After the war, he led his fourth expedition to Antarctica, the largest ever attempted to this date, and more than 500,000 miles of the continent were mapped by his planes. In 1955, he led his fifth and final expedition to Antarctica. He died in 1957.

Here are a couple of asides:

- That first flight has been shrouded in controversy because of discrepancies between the Admiral’s hand-written notes and later land-based calculations. Despite the differing opinions, Byrd is generally credited with being the first to pilot and aircraft to the Pole.

- The young Fokker was something of a party boy and could often be seen pacing his planes down the tarmac in a new convertible Packard.

- Co-pilot Floyd Bennet is remembered today as the name of the airfield in Brooklyn, Floyd Bennett Field.

- The Admiral was an energetic promoter and Byrd organized his own effort to fly an airplane over the North Pole. He persuaded American millionaires John D. Rockefeller and Edsel Ford, who gave $25,000 each and other people of wealth to donate to his expedition. Volunteers, especially from the naval reserves, joined him at no charge. Shrewdly, Byrd negotiated with the news media for payments in exchange for stories. One document found in Byrd’s papers was a contract with Current News Features This guaranteed Byrd at least $18,000, even if Byrd failed to reach the North Pole. Another with the Pond agency promised Byrd a lecture tour after the expedition. From this money Byrd leased a ship and purchased an airplane. The selection of an airplane was the most critical aspect of Byrd’s expedition.

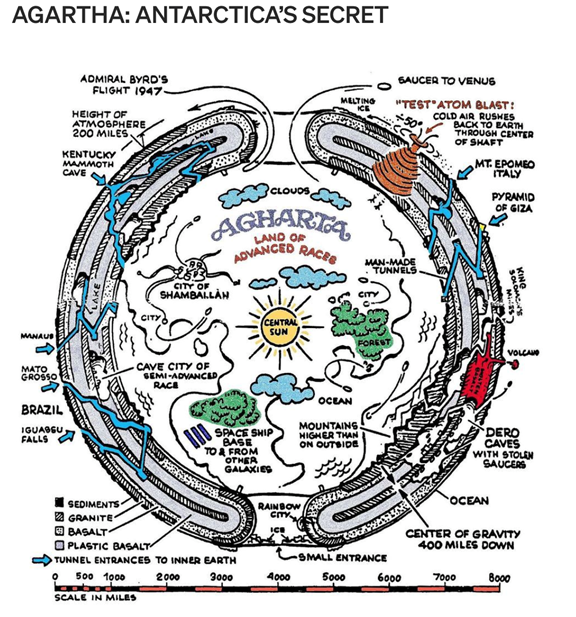

- Byrd allegedly kept a secret diary in which he wrote of his encounter with a lost civilization in Antarctica. According to Hollow Earth theorists, Byrd met an ancient race underground in the South Pole. Aspects of this ‘alleged’ diary follow along well worn alien abduction, area 51, classic sifi such as ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ and ‘Angry Red Planet’ and even an episode of the fifties TV show ‘Superman’ tropes warning humans of their folly in ‘playing’ with nuclear weapons..

For thousands of years, people all over the world have written legends about Agartha (sometimes called Agarta or Agarthi), the underground city. Did Byrd find it?

Great fun to imagine!!